FlashAttention-1

In this 2022 paper, the authors ask if efficiency in computing exact attention can enable transformers parse larger sequences and help overcome runtime and memory challenges for long sequences.

They note that

- approximate attention techiques, a common approach to overcoming the quadratic time and space complexity of self-attention, tend to ignore overheads from memory access (IO speeds in GPUs).

- as shown in Ivanov et. al, most operations on modern GPUs are bottlenecked by the memory bandwidth and fall short of using the available compute efficiently.

Thus, the authors argue for using operations that account for the reads and writes to different levels of fast and slow memory, i.e. introduction of IO-awareness in algorithms, on modern accelerators (eg. SRAM vs High Bandwidth Memory in modern GPUs). With this, they focus on the attention computation to

- reduce the number of memory access by computing the exact softmax without multiple accesses to the whole input. This helps speed up the forward pass during training as well as inference.

- not store the large intermediate attention matrix for the backward pass. This speeds up the gradient computation during training.

The authors introduce the FlashAttention algorithm that uses tiling to compute the streaming softmax over blocks of the input and enables both (1) the incremental calculation of the final softmax matrix while significantly reducing the number of global memory access making the forward pass more performant, as well as (2) storage of block statistics instead of the large intermediate attention matrix for the gradient computation thus making the backward pass faster eventhough the number of operations increase.

Standard Attention

Given input sequences \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\)

\[ \begin{align} \mathbf{S} &= \mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^{T} &&\in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N} \\ \mathbf{P} &= \text{softmax}(\mathbf{S}) &&\in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N} \\ \mathbf{O} &= \mathbf{P}\mathbf{V} &&\in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d} \end{align} \]

where,

\(N\) is the sequence length

\(d\) is the head dimension

Often, \(N \gg d\) (e.g., for GPT2, \(N = 1024\) and \(d = 64\)).

Standard Attention Forward Algorithm

Require: Matrices \(\mathbf{Q},\mathbf{K},\mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\) in HBM.

- Load \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}\) by blocks from HBM, compute \(\mathbf{S}\) and write it to HBM.

- Read \(\mathbf{S}\) from HBM, compute \(P\) and write it to HBM.

- Load \(\mathbf{P}, \mathbf{V}\) by blocks from HBM, compute \(\mathbf{O}\) and write to HBM.

- Return \(\mathbf{O}\).

The standard attention (forward) algorithm materializes the matrices \(\mathbf{S}\) and \(\mathbf{P}\) to the HBM which takes \(O(N^2)\) memory. As some or most of the operations are memory-bound, the large number of memory accesses translate to slow wall-clock time.

Standard Attention Backward Algorithm

Require: Matrices \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}, \mathbf{dO} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}, \mathbf{P} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}\) in HBM.

- Load \(\mathbf{P}, \mathbf{dO}\) by blocks from HBM, compute \(\mathbf{dV} = \mathbf{P}^T\mathbf{dO} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\), write \(\mathbf{dV}\) to HBM.

- Load \(\mathbf{dO}, \mathbf{V}\) by blocks from HBM, compute \(\mathbf{dP} = \mathbf{dO}\mathbf{V}^T \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}\), write \(\mathbf{dP}\) to HBM.

- Read \(\mathbf{P}, \mathbf{dP}\) from HBM, compute \(\mathbf{dS} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}\), where \(dS_{ij} = P_{ij}(dP_{ij} - \sum_{l}P_{il}dP_{il})\), write \(\mathbf{dS}\) to HBM.

- Load \(\mathbf{dS}\) and \(\mathbf{K}\) by blocks from HBM, compute \(dQ = dSK\), write \(dQ\) to HBM.

- Load \(\mathbf{dS}\) and \(\mathbf{Q}\) by blocks from HBM, compute \(\mathbf{dK} = \mathbf{dS}^T\mathbf{Q}\), write \(\mathbf{dK}\) to HBM.

- Return \(\mathbf{dQ}, \mathbf{dK}, \mathbf{dV}\).

To compute the gradients with respect to \(\mathbf{dQ}, \mathbf{dK}, \mathbf{dV}\), the standard backward algorithm relies on the large intermediate matrix \(\mathbf{P} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}\) to calculate \(\mathbf{dP}\) which is also materialized to the HBM in addition to \(\mathbf{dS}\).

FlashAttention

To achieve the goal of computing attention with significantly reduced HBM access, the authors use tiling and re-computation.

The main idea is that we split the inputs \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}\) into blocks, load them from slow HBM to fast SRAM, then compute the attention output with respect to those blocks. By scaling the output of each block by the right normalization factor before adding them up, we get the correct result at the end.

Tiling for attention outputs with respect to blocks

This is achieved by applying tiling to the online softmax reduction outlined by Milakov and Gimelshein.

For vector \(x^{(k)} \in \mathbb{R}^B\), \(B\) being the size of the block and \(k\) denoting that \(x^{(k)}\) \(k_{\text{th}}\) block of some vector \(x\) of size \(\gg B\)

\[ \begin{align} m(x^{(k)}) & := \underset{i}{\text{max }} x^{(k)}_i \\ f(x^{(k)}) & := [e^{x^{(k)}_1 - m(x^{(k)})} ... e^{x^{(k)}_B - m(x^{(k)})}] \\ \ell(x^{(k)}) & := \underset{i}{\sum} f(x^{(k)})_i \end{align} \]

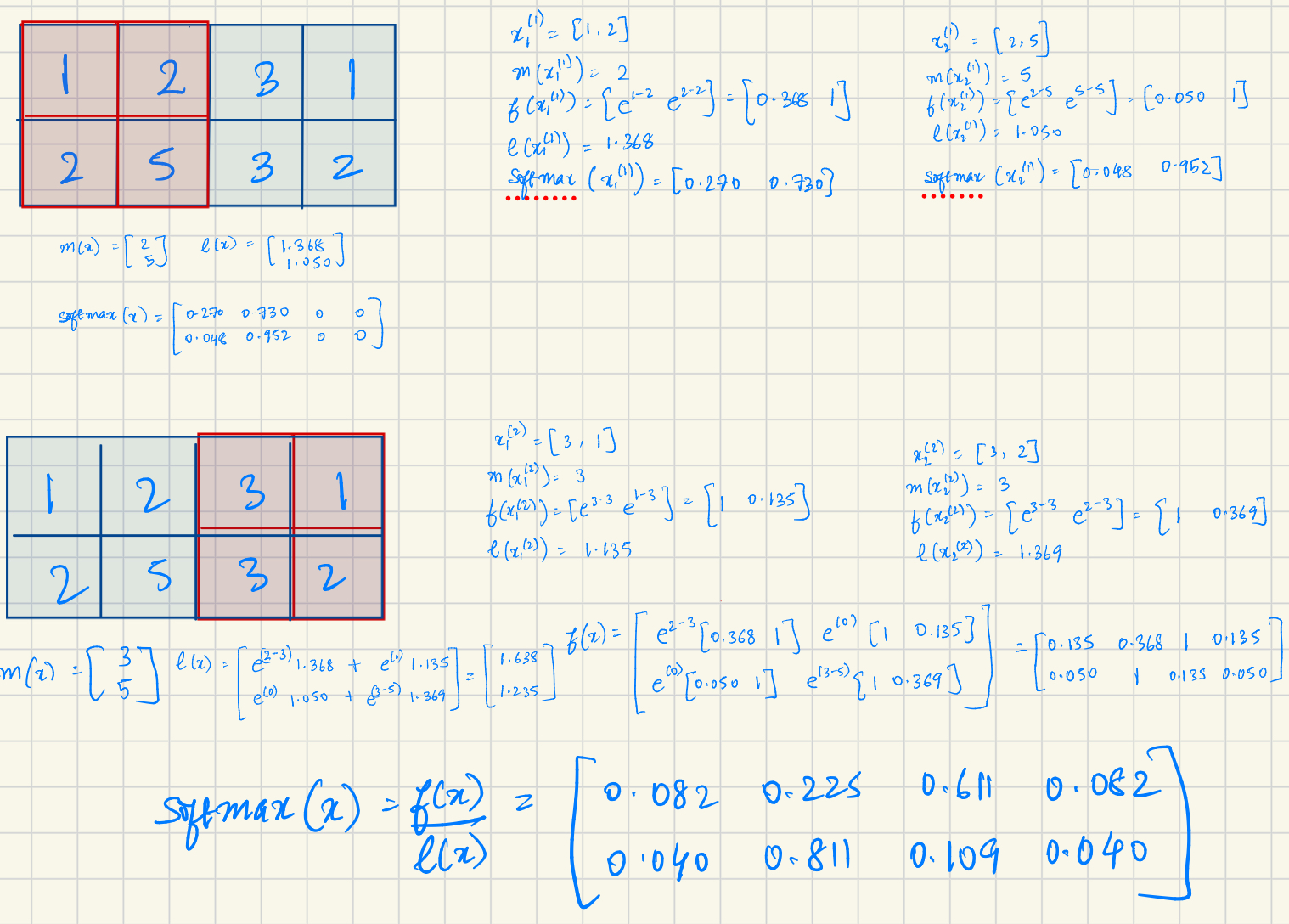

Thus, softmax can be calculated blockwise using the normalization statistics \((m(x), \ell(x))\).

For vectors \(x^{(1)}, x^{(2)} \in \mathbb{R}^B\), the softmax of the concatenated \(x = [x^{(1)} x^{(2)}] \in \mathbb{R}^{2B}\) as:

\[ \begin{align} m(x) &= m([x^{(1)} x^{(2)}]) &&= \text{max}(m(x^{(1)}), m(x^{(2)})) \\ \ell(x) &= \ell([x^{(1)} x^{(2)}]) &&= e^{m(x^{(1)}) - m(x)}\ell(x^{(1)}) e^{m(x^{(2)}) - m(x)}\ell(x^{(2)}) \end{align} \]

Using \(m(x)\) and \(\ell(x)\), \(f(x)\) and \(\text{softmax}(x)\) can be calculated as:

\[ \begin{align} f(x) &= [e^{m(x^{(1)}) - m(x)}f(x^{(1)}) e^{m(x^{(2)}) - m(x)}f(x^{(2)})] \\ \text{softmax}(x) &= \frac{f(x)}{\ell(x)} \end{align} \]

Here is a small hand-worked example:

Tiling enables the implementation of all computation steps in one kernel without multiple HBM access for reads and writes, i.e., it enables us to load input from HBM, perform computation (matrix multiply, softmax, optionally masking and dropout, matrix multiply), then write result back to HBM in one kernel.

FlashAttention Algorithm (Forward)

The authors prove that this algorithm returns \(\mathbf{O} = \text{softmax}(\mathbf{Q}\mathbf{K}^T\mathbf{V})\) with \(O(N^2d)\) FLOPs and requires \(O(N)\) additional memory beyond inputs and output to store \(m\) and \(\ell\).

Require: Matrices \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\) in HBM, on-chip SRAM of size \(M\).

- Set block sizes \(B_c = \lceil \frac{M}{4d} \rceil\), \(B_r = \min(\lceil \frac{M}{4d} \rceil, d)\).

- Initialize \(\mathbf{O} = (0)_{N \times d} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\), \(\ell = (0)_{N} \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\), \({m} = (-\infty)_{N} \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\) in HBM.

- Divide \(\mathbf{Q}\) into \(T_r = \lceil \frac{N}{B_r} \rceil\) blocks \(\mathbf{Q}_1, \dots, \mathbf{Q}_{T_r}\), of size \(B_r \times d\) each, and divide \(\mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}\) into \(T_c = \lceil \frac{N}{B_c} \rceil\) blocks \(\mathbf{K}_1, \dots, \mathbf{K}_{T_c}\) and \(\mathbf{V}_1, \dots, \mathbf{V}_{T_c}\), of size \(B_c \times d\) each.

- Divide \(\mathbf{O}\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(\mathbf{O}_1, \dots, \mathbf{O}_{T_r}\), of size \(B_r \times d\) each, divide \(\ell\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(\ell_1, \dots, \ell_{T_r}\), of size \(B_r\) each, divide \(m\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(m_1, \dots, m_{T_r}\), of size \(B_r\) each.

- for \(1 \le j \le T_c\) do

- \(\quad\) Load \(\mathbf{K}_j, \mathbf{V}_j\) from HBM to on-chip SRAM.

- \(\quad\) for \(1 \le i \le T_r\) do

- \(\qquad\) Load \(\mathbf{Q}_i, \mathbf{O}_i, \ell_i, m_i\) from HBM to on-chip SRAM.

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{S}_{ij} = \mathbf{Q}_i \mathbf{K}_j^T \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\tilde{m}_{ij} = \text{rowmax}(\mathbf{S}_{ij}) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r}\), \(\mathbf{\tilde{P}}_{ij} = \exp(\mathbf{S}_{ij} - \tilde{m}_{ij}) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\) (pointwise), \(\mathbf{\tilde{\ell}}_{ij} = \text{rowsum}(\mathbf{\tilde{P}}_{ij}) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(m_i^{\text{new}} = \max(m_i, \tilde{m}_{ij}) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r}\), \(\ell_i^{\text{new}} = e^{m_i - m_i^{\text{new}}} \ell_i + e^{\tilde{m}_{ij} - m_i^{\text{new}}} \mathbf{\tilde{\ell}}_{ij} \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r}\).

- \(\qquad\) Write \(\mathbf{O}_i \leftarrow \text{diag}(\ell_i^{\text{new}})^{-1} (\text{diag}(\ell_i) e^{m_i - m_i^{\text{new}}} \mathbf{O}_i + e^{\tilde{m}_{ij} - m_i^{\text{new}}} \mathbf{\tilde{P}}_{ij} \mathbf{V}_j)\) to HBM.1

- \(\qquad\) Write \(\ell_i \leftarrow \ell_i^{\text{new}}\), \(m_i \leftarrow m_i^{\text{new}}\) to HBM.

- \(\quad\) end for

- end for

- Return \(\mathbf{O}\).

Unlike tiling in most GMM algorithms, this algorithm does 1D block tiling. It doesn’t tile on \(d\) and assumes the head dimension will always fit within the blocks.

An A100 has a configurable 164KB SRAM per SM.

Assuming the availability of 128KB and using fp16/bf16 (2 bytes to represent a number) for all our computations,

we can calculate \(M\) first: \[

\begin{align}

M &= \frac{\text{Total Available Bytes}}{\text{ Bytes to represent a number}}&&= \frac{128 \times 1024}{2} &&= 65536

\end{align}

\]

With \(M\), we can calculate \(B_c\) and \(B_r\):

\[ \begin{align} B_c &= \lceil \frac{M}{4 \times d} \rceil &&= \lceil \frac{65536}{4 \times 64} \rceil &&= 256 \\ B_r &= \min(\lceil \frac{M}{4 \times d} \rceil, d) &&= \min(\lceil \frac{65536}{4 \times 64} \rceil, 64) &&= 64 \end{align} \]

Assuming \(N = 1024\) (used in the paper), we can calculate tile sizes as:

\[

\begin{align}

T_r &= \lceil \frac{N}{B_r} \rceil &&= \frac{1024}{64}&&= 16 \\

T_c &= \lceil \frac{N}{B_c} \rceil &&= \frac{1024}{256}&&= 4

\end{align}

\]

Re-computation of S and P for backward pass

While the tiling trick enables speed-ups for inference, i.e. during the forward pass through the transformer, the backward pass typically relies on the intermediate matrices \(\mathbf{S},\mathbf{P} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}\) for the gradient computation with respect to \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}\).

To avoid storing the \(O(N^2)\) intermediate values for the backward pass, the authors instead store the softmax normalization statistics \((m, \ell)\) and re-compute \(\mathbf{S}, \mathbf{P}\) in the SRAM during the backward pass.

The authors are increasing FLOPs in order to re-compute \(\mathbf{S}\) and \(\mathbf{P}\) fully in the SRAM and argue that this trade-off leads to more efficient use of the available hardware leading to an increased overall performance.

Using some scalar loss function \(\phi\),

\[

\begin{align}

\text{Let } \mathbf{dO} &\in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d},&&(\text{where } \mathbf{dO} \text{ denotes } \frac{\delta \phi}{\delta \mathbf{O}}) \\

\text{We want } \mathbf{dQ}, \mathbf{dK}, \mathbf{dV} &\in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d},&&(\text{where } \mathbf{dQ}, \mathbf{dK}, \mathbf{dV} \text{ denote } \frac{\delta \phi}{\delta \mathbf{Q}},\frac{\delta \phi}{\delta \mathbf{K}},\frac{\delta \phi}{\delta \mathbf{V}} \text{ resp.})

\end{align}

\]

Calculating \(\mathbf{dV}\) using chain rule, we get \(\mathbf{dV} = \mathbf{P}^T\mathbf{dO}\). This can be expressed using \(\mathbf{Q}\), \(\mathbf{K}\) and the normalizing statistic \(\ell\) (calculated during the forward pass) completely in the SRAM:

\[ \begin{align} dv_j &= \underset{i}{\sum} P_{ij}do_i &&= \underset{i}{\sum} \frac{e^{q^{T}_{i}k_j}}{\ell_i} do_i \end{align} \]

To calculate the gradients \(\mathbf{dQ}\) and \(\mathbf{dK}\), the gradients \(\mathbf{dP}\) and \(\mathbf{dS}\) are required. \(\mathbf{dP}\) can be calculated using \(\mathbf{dO}\) and \(\mathbf{V}\): \(\mathbf{dV} = \mathbf{dO}\mathbf{V}^T\) and thus, \[ \begin{align} dP_{ij} = do_{i}^Tv_j \end{align} \]

The calculation of \(\mathbf{dS}\) we have to start with the Jacobian of softmax2:

\[ \begin{align} y &= \text{softmax}(x) \\ J(y) &= \text{diag}(y) - yy^T \end{align} \]

Since \(P_{i:} = \text{softmax}(S_{i:})\), we have:

\[ \begin{align} dS_{i:} &= (\text{diag}(P_{i:}) - P_{i:}P^{T}_{i:})dP_{i:} = P_{i:} \odot dP_{i:} - (P^TdP_{i:})P_{i:} \end{align} \] where \(\odot\) denotes pointwise multiplication.

Define \[ \begin{align} D_{i} &= P^{T}_{i:}dP_{i:} = \underset{j}{\sum} \frac{e^{q^T_ik_j}}{\ell_i} do^T_iv_j = do^T_i \underset{j}{\sum} \frac{e^{q^T_ik_j}}{\ell_i} v_j = do^T_io_i \end{align} \]

then,

\[

\begin{align}

dS_{i:} &= P_{i:} \odot dP_{i:} - D_iP_{i:}

\end{align}

\]

Making \[ \begin{align} dS_{ij} &= P_{ij}dP_{ij} - D_iP_{ij} = P_{ij}(dP_{ij} - D_{i}) \end{align} \]

Now we can calculate the gradients for \(\mathbf{dQ}\) and \(\mathbf{dK}\). \(S_{ij} = q^T_ik_j\), therefore

\[

\begin{align}

dq_i = \underset{j}{\sum} dS_{ij}k_{j} = \underset{j}{\sum} P_{ij}(dP_{ij} - D_i)k_j = \underset{j}{\sum}\frac{e^{q^{T}_ik_j}}{\ell_i} (do^T_iv_j - D_i)k_j

\end{align}

\]

and similarly, \[ \begin{align} dk_j = \underset{j}{\sum} dS_{ij}q_{i} = \underset{j}{\sum} P_{ij}(dP_{ij} - D_i)q_i = \underset{j}{\sum} \frac{e^{q^T_ik_j}}{\ell_i} (do^T_iv_j - D_i)q_i \end{align} \]

Thus, the backward pass can be computed with \(O(N)\) extra memory.

FlashAttention Backward Pass

Require: Matrices \(\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}, \mathbf{O}, \mathbf{dO} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\) in HBM, vectors \(\ell, m \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\) in HBM, on-chip SRAM of size \(M\), softmax scaling constant \(\tau \in \mathbb{R}\), masking function \(\text{MASK}\), dropout probability \(p_{\text{drop}}\), pseudo-random number generator state \(\mathcal{R}\) from the forward pass.

- Set the pseudo-random number generator state to \(\mathcal{R}\).

- Set block sizes \(B_c = \lceil \frac{M}{4d} \rceil, B_r = \min(\lceil \frac{M}{4d} \rceil, d)\).

- Divide \(\mathbf{Q}\) into \(T_r = \lceil \frac{N}{B_r} \rceil\) blocks \(\mathbf{Q}_1, \dots, \mathbf{Q}_{T_r}\) of size \(B_r \times d\) each, and divide \(\mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}\) in to \(T_c = \lceil \frac{N}{B_c} \rceil\) blocks \(\mathbf{K}_1, \dots, \mathbf{K}_{T_c}\) and \(\mathbf{V}_1, \dots, \mathbf{V}_{T_c}\), of size \(B_c \times d\) each.

- Divide \(\mathbf{O}\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(\mathbf{O}_1, \dots, \mathbf{O}_{T_r}\) of size \(B_r \times d\) each, divide \(\mathbf{dO}\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(\mathbf{dO}_1, \dots, \mathbf{dO}_{T_r}\) of size \(B_r \times d\) each, divide \(\ell\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(\ell_1, \dots, \ell_{T_r}\) of size \(B_r\) each, divide \(m\) into \(T_r\) blocks \(m_1, \dots, m_{T_r}\) of size \(B_r\) each.

- Initialize \(\mathbf{dQ} = (0)_{N \times d}\) in HBM and divide it into \(T_r\) blocks \(\mathbf{dQ}_1, \dots, \mathbf{dQ}_{T_r}\) of size \(B_r \times d\) each. Initialize \(\mathbf{dK} = (0)_{N \times d}, \mathbf{dV} = (0)_{N \times d}\) in HBM and divide \(\mathbf{dK}, \mathbf{dV}\) in to \(T_c\) blocks \(\mathbf{dK}_1, \dots, \mathbf{dK}_{T_c}\) and \(\mathbf{dV}_1, \dots, \mathbf{dV}_{T_c}\), of size \(B_c \times d\) each.

- for \(1 \le j \le T_c\) do

- \(\quad\) Load \(\mathbf{K}_j, \mathbf{V}_j\) from HBM to on-chip SRAM.

- \(\quad\) Initialize \(\tilde{\mathbf{dK}}_j = (0)_{B_c \times d}, \tilde{\mathbf{dV}}_j = (0)_{B_c \times d}\) on SRAM.

- \(\quad\) for \(1 \le i \le T_r\) do

- \(\qquad\) Load \(\mathbf{Q}_i, \mathbf{O}_i, \mathbf{dO}_i, \mathbf{dQ}_i, \ell_i, m_i\) from HBM to on-chip SRAM.

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{S}_{ij} = \tau \mathbf{Q}_i \mathbf{K}_j^T \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{S}_{ij}^{\text{masked}} = \text{MASK}(\mathbf{S}_{ij})\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{P}_{ij} = \text{diag}(\ell_i)^{-1} \exp(\mathbf{S}_{ij}^{\text{masked}} - m_i) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute dropout mask \(\mathbf{Z}_{ij} \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\) where each entry has value \(\frac{1}{1-p_{drop}}\) with probability \(1 - p_{drop}\) and value \(0\) with probability \(p_{drop}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{P}_{ij}^{\text{dropped}} = \mathbf{P}_{ij} \odot \mathbf{Z}_{ij}\) (pointwise multiply).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\tilde{\mathbf{dV}}_j \leftarrow \tilde{\mathbf{dV}}_j + (\mathbf{P}_{ij}^{\text{dropped}})^T \mathbf{dO}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{B_c \times d}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{dP}_{ij}^{\text{dropped}} = \mathbf{dO}_i \mathbf{V}_j^T \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{dP}_{ij} = \mathbf{dP}_{ij}^{\text{dropped}} \odot \mathbf{Z}_{ij}\) (pointwise multiply).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{D}_i = \text{rowsum}(\mathbf{dO}_i \odot \mathbf{O}_i) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r}\).

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\mathbf{dS}_{ij} = \mathbf{P}_{ij} \odot (\mathbf{dP}_{ij} - \mathbf{D}_i) \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\).

- \(\qquad\) Write \(\mathbf{dQ}_i \leftarrow \mathbf{dQ}_i + \tau \mathbf{dS}_{ij} \mathbf{K}_j \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times d}\) to HBM.

- \(\qquad\) On chip, compute \(\tilde{\mathbf{dK}}_j \leftarrow \tilde{\mathbf{dK}}_j + \tau \mathbf{dS}_{ij}^T \mathbf{Q}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{B_c \times d}\).

- \(\quad\) end for

- \(\quad\) Write \(\mathbf{dK}_j \leftarrow \tilde{\mathbf{dK}}_j, \mathbf{dV}_j \leftarrow \tilde{\mathbf{dV}}_j\) to HBM.

- end for

- Return \(\mathbf{dQ}, \mathbf{dK}, \mathbf{dV}\).

Decreased Memory Accesses for Improved Performance

Quantifying the Complexity

The forward algorithm has the same time complexity \(O(N^2d)\) as the standard softmax algorithm and uses \(O(N)\) extra space to save \((m, \ell)\).

The standard softmax with \(\mathbf{Q},\mathbf{K},\mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times d}\) takes \(O(N^2d)\) for \(\mathbf{QK}^T\)3, \(O(N^2)\) for \(\text{softmax}(\mathbf{S})\), \(\text{rowsum}(\mathbf{S})\), \(\text{rowmax}(\mathbf{S})\) and then \(O(N^2d)\) again for \(\mathbf{PV}\).

The tiled, blockwise softmax used in FlashAttention is also dominated by the matrix multiplication. It operates on \(\mathbf{Q} \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times d}\) and \(\mathbf{K},\mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{B_c \times d}\), taking \(O(B_rB_cd)\) for \(\mathbf{Q}_i\mathbf{K}_j^T\), \(\tilde{\mathbf{P}}_{ij}\mathbf{V}_j\) and \(O(B_rB_c)\) for the operations on \(\mathbf{S}_{ij}\) like calculating \(\text{softmax}, \ell, m\), making the time-complexity here \(O(B_rB_cd)\). These are looped \(T_rT_c\) times, making the final time complexity:

\[ \begin{align} O(T_rT_cB_rB_cd) &= O(\frac{N}{B_r}\frac{N}{B_c}B_rB_cd) = && O(N^2d) \end{align} \]

The increase in performance comes from the reduction in HBM accesses. The standard softmax incurs \(\Theta(Nd + N^2)\) HBM accesses whereas the FlashAttention algorithm requires \(\Theta(\frac{N^2d^2}{M})\) where \(M\) is the size of SRAM. In settings where \(M \gg d\), this algorithm should lead to significantly reduced memory accesses over the standard attention algorithm.

The standard softmax requires \(\Theta(Nd + N^2)\) for reading \(\mathbf{Q},\mathbf{K}\) and writing \(\mathbf{S}\). It then needs \(\Theta(N^2)\) for computing \(\mathbf{P}\) and finally, another \(\Theta(Nd + N^2)\) for computing and writing \(\mathbf{O}\). Overall, the standard softmax incurs \(\Theta(Nd + N^2)\) HBM accesses.

In comparison, the FlashAttention algorithm loads each element from \(\mathbf{K},\mathbf{V}\) once and makes \(T_c\) passes over \(\mathbf{Q}\) and \(\mathbf{O}\) and thus the HBM accesses here \(\Theta(Nd + NdT_c) = \Theta(NdT_c)\).

Within the blockwise iterations, we need \(\mathbf{K}_j\) and \(\mathbf{V}_j\) of size \(B_c \times d\) to fit into the SRAM (on-chip memory). Therefore,

\[ \begin{align} B_cd &= O(M) &&\Leftrightarrow B_c = O(\frac{M}{d}) \end{align} \]

Similarly, \(\mathbf{Q}_i\) and \(\mathbf{O}_j\) of size \(B_r \times d\) have to fit into the SRAM.

\[

\begin{align}

B_rd &= O(M) &&\Leftrightarrow B_r = O(\frac{M}{d})

\end{align}

\]

\(\mathbf{S}_{ij} \in \mathbb{R}^{B_r \times B_c}\) also has to fit in the SRAM, and so \[ \begin{align} B_rB_c = O(M) \end{align} \]

Setting: \[ \begin{align} B_c &= \Theta(\frac{M}{d}),&& B_r = \Theta(\text{min}(\frac{M}{d}, \frac{M}{B_c})) = \Theta(\text{min}(\frac{M}{d}, d)) \end{align} \]

We get, \[ \begin{align} T_c = \frac{N}{B_c} = \Theta(\frac{Nd}{M}) \end{align} \]

And therefore, the number of HBM accesses is:

\[

\begin{align}

\Theta(NdT_c) = \Theta(\frac{N^2d^2}{M})

\end{align}

\]

Implications for the user

- Larger block sizes \(B_c\) and \(B_r\) will lead to lesser HBM accesses and increases amount of GPU time spent on FLOPs. The amount of available SRAM per chip dictates how large the block sizes can be.

- Increased FLOPs will result in faster runtime till the bottlenecks shift from memory bandwidth (to arithmetic operations in the ideal case, or, in the worst case, resource constraints).

When we consider some commonly used GPUs, there a few things that we can expect about performance gains:

| GPU | Arch | SMs | SRAM4 | VRAM | Memory Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | Tesla T4 | 46 | 64KB | 16 GB | 320 GB/sec |

| V100 | Volta GV100 | 80 | 96KB | 16 GB | 760 GB/sec |

| A10g | Ampere GA10x | 84 | 96KB | 24 GB | 600 GB/sec |

| A100 | Ampere A100 | 108 | 164KB | 40 / 80 GB | 1555 GB/sec |

| H100 | Hopper H100 | 114 | 228KB | 80 GB | 2039 GB/sec |

- During Inference: On a GPU like T4, even small models like llama3.2-3B that can fit within its VRAM will see only marginal gains at full sequence length (if any) because the block size will have to be very small due to the small SRAM. Any real improvements would need exploit additional characteristics of inference settings.

- During Training: On T4, there is likely no performance gain to be expected when dealing with realistic sequence lengths. The A10 might be only a slightly better budget candidate to T4 even at twice the cost per GPU, but any real training would need something like an A100 or H100.

- On the other hand, very small models / small models in small sequence settings, if run on GPUs like A/H100 using all of the available resource, might not be memory bound in which case

FlashAttentionmight add additional computation steps.

FlashAttention-2

This paper that was published in 2023 tries to make FlashAttention even more efficient. It looks at modern GPU architectures to introduce better usage of specialized on-chip devices and enable better parallelism and work partitioning.

As motivation, the author points out that the forward algorithm reaches only 30-50% of the theoretical maximum FLOPs/seconds and the backward algorithm reaches only 25-35% of the maximum FLOPs/seconds of an NVIDIA A100 GPU. They contrast this with GEMM, which typically reaches up to 80-90% of the theoretical maximum throughput.

Separating Matrix and Non-Matrix Ops [WIP]

The first insight is that modern GPUs have on-chip devices specifically to optimize matrix operations(e.g. NVIDIA GPUs have Tensor Cores and AMD GPUs have matrix cores) allowing matrix operations to run at a much higher throughput than non-matrix operations. The authors note that on an A100, a non-matmul FLOP (FP32) is 16x more expensive than a matmul FLOP.

| GPU | Arch | FP16 MMA | BF16 MMA | Tensor FP16MMA | FP32 MMA | Tensor FP32MMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | Tesla T4 | 16.2 | 16.2 | 65 | 8.1 | NA |

| A10g | Ampere GA10x | 35 | 70 | 70 | 35 | 70 |

| A100 | Ampere A100 | 78 | 39 | 312 | 19.5 | 312 |

| H100 | Hopper H100 | 133.8 | 133.8 | 989.4 | 66.9 | 494.7 |

References

- Dao, Tri, Daniel Y. Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. “FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness.” Preprint, submitted May 2022. arXiv:2205.14135. https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.14135.

- Ivanov, Andrei, Nikoli Dryden, Tal Ben-Nun, Shigang Li, and Torsten Hoefler. “Data Movement Is All You Need: A Case Study on Optimizing Transformers.” Preprint, submitted July 2020. arXiv:2007.00072. https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.00072.

- Modal, GPU Glossary

- Hwu, Wen-mei, and David Kirk. Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach. 4th ed. Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2023.

- Milakov, Maxim, and Natalia Gimelshein. “Online Normalizer Calculation for Softmax.” Preprint, submitted May 2018. arXiv:1805.02867. http://arxiv.org/abs/1805.02867.

- NVIDIA GPU white-papers (Tesla T4, Volta GV100, Ampere A10x, Ampere A100, Hopper H100)

- Bohan Li, Donghan Yu, Ge Huang, and Ryan Tibshirani: Fall 2015 Convex Optimization Notes for Lecture 19.

- Dao, Tri. “FlashAttention-2: Faster Attention with Better Parallelism and Work Partitioning.” Preprint, submitted July, 2023. arXiv:2307.08691. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.08691.

Footnotes

Equivalent numpy expression:

O_i = (l_i[..., np.newaxis] * np.exp(m_i - m_i_new) * O_i + np.exp(m_ij - m_i_new)*(P_ij @ V_j)) / l_i_new[..., np.newaxis].↩︎softmaxis a vector function and the Jacobian is the matrix formed by the partial derivatives of a vector function.↩︎Given \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}, B \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}\), then total operation count for matrix-multiplication \(AB\) is \(2mnp\).↩︎

Modern NVIDIA GPUs have combined L1 data cache and shared memory (SRAM) and the exact memory reserved for both is configurable.↩︎